Eternal return’s absence in Death.

There is a book I used to read, as a little girl, that spoke of Death and Fairies. It wasn’t fantasy, it felt more like poetic philosophy disguised as a children’s book: exciting, beautiful, and most importantly, it addressed that thing that scares us the most, Death.

I have been wanting to write a blog about Death for a while now, months in fact, because my cat died whilst I was travelling, and it broke my heart. From my experience, and based of the people I frequent the most, Death is not usually at the top of peoples minds unless it directly affects them, wether personally or through a loved one, and is a topic that is avoided by those privileged enough not to see it. Actually though, it is what we all have in common, and what we all fear, in some form or another.

In the story, a child discovers a small fairy who visibly needs her help, as she seems weak and vulnerable. They become friends and the fairy shares her universe with her, and explains that the fairies become ill and die when they are forgotten about, because they are in fact the souls of those who have passed away. The little girl takes it upon herself to meet up with the people who have lost their loved ones, and make them talk about them, so that their memories of them resurface, and so that they are never to be forgotten. In the act of talking, exists the act of remembering, and in that combination of love and life, friends and families cured the fairies by bringing into the present, those who had been lost to the past. It turns out, it was more painful for both the dead and the living, to disregard Death as taboo, something to be avoided and feared. The more it was discussed, and the more it became a part of life, which is the opposite of death but not a contradiction, the less feared it became.

I do not wish to talk about Death, and therefore Grief, in the traditional sense, but rather the ways in which people forget to, and forget about it. I understand the taboo behind it, of course, because how do you discuss Death to a person who may have experienced it worse than anything you can understand, when they might have lost the person they most cared for, and you have not. Death is not fair, and it is with a privileged stance that I approach it, because although I have had my share and sorrow in it, I see and live very little of it. Mainly, I am curious about the ways we discuss death, and those ways we represent it, in different areas and epochs of society, and through such cultural and religious variety. I cannot express not research all the aspects of Death worth exploring, but for now, in this little blog, I want to explore its presence in Thanatos, Puss in Boots and Irvin Yalom, a curiously strange melange.

You may have heard of Thanatos or Hades, whose roles in Death are often confused, as they are both considered its God. Whilst the confusion is understandable, their roles are rather different, whereby Hades is considered the most powerful of the two as the Ruler of the Underworld, and Thanatos is known as the personification of Death itself. When I was little, I used to love those little Greek Myth stories; they were simplified of course, and lightened, for the darkness in some could be too heavy for the mind of a small child (or is it ?). Recently, I discovered an audio book by Stephen Fry, on Greek Mythology. I skipped to all the parts that speak of Death, with the intention of listening to the rest in another moment. Death, it turns out, is just as important to the Greeks as Life itself. They believe that once you die and are buried, your soul leaves your body and is accompanied to the entrance of the underworld by Hermes (the god of trade, travellers and merchants), to a boat, rowed by Charon, that carries the spirits across the Acheron (river of woe) or the Styx (river of hate). These two rivers are the divide between the Land of the Living and the Land of the Dead. Usually, and from what I understand of Greek Mythology, the Land of the Dead is divided into three realms: Elysium Fields (you will find this name perpetuated in many different forms throughout society, for example in A Streetcar Named Desire and the famous Champs Elyse in Paris), the Land of Hades, and the Pits of Tartarus (these each also go by other names). Generally then, these three realms divide the Dead, and therefore in some ways, the Living, into ‘The Good’, ‘The Bad’ and ‘The Forgotten’ (which is really a variable for those who are average). From what we know, we can imagine Elysium as resembling a sort of Greek pagan version of the famous Christian Heaven, where the good souls can begin a bright new state of being, their memories erased so that they can continue forwards without sufferings of the past. The spirits that are condemned to the dark pits of Tartarus are condemned to an eternity of torment and suffering, whereas the spirits who did not significantly impact the lives of others were sent to the Land of Hades, to wander for all eternity.

I have a certain fascination with this idea, how Death can be so dictated by the life you lead before it, and therefore, we find again Kundera’s idea of Eternal return: The life you lead before Death, will end up being dictated by your life after it, by fear of your actions leading you to the broad idea of Hell. The final destination, as it appears here, is solely dependant on the life you lead. Therefore, life and death are equally as important, as death actually, ends up lasting longer than life itself, and with more potential for suffering and torment.

In 1697, the original version of Puss in Boots was written by Italian Straparola, but it is French Charles Perrault’s version that is known best today. In general, it tells the tale of a clever cat in boots who helps a commoner become a noble and marry a princess. There have been many adaptations of this throughout history, including some new branches of the story, the most recent being ‘Puss in Boots: The Last Wish‘, which hit the cinemas in 2022.

SPOILER ALERT.

In this modern twist, Puss in Boots faces the inevitability of Death personified. As he confronts the reality of being left with one last life, he faces an existential depression, and sets off to wish his life back. Death in this story is represented as a sickle wielding red eyed wolf, and appears often in violent confrontation with the cat, who flees as quickly as possible each time. He dreams about him and fears him, constantly. I find that it gets interesting when we understand that the wolf’s dislike of the cat is not a personal attack on his character, but rather a representation of his disgust for Puss in Boots’ disregard for life. This turns the viewers opinion of the wolf on its head: the protagonist (Puss in Boots) becomes his own antagonist (Puss in Boots), taking that role away from the wolf. After many battles and escapes, the cat realises that he cannot beat death, because no one can, and turns instead to embrace his last life. Death decides to walk away, with the promise of return. Puss in Boots accepts his fate, knowing that he will live his life as well as he can. t

The personification here is extremely clever, where the wolf is depicted as the bad guy, the antagonist, and is vastly feared. As it turns out, Puss in Boots, the main character, is in fact his own worst enemy, because of his lack of care for the life he is living. In the wolfs presence, the cat finally faces his fear, and in doing so, the fear disappears. It is a great metaphor, although understandably, one that is considerably harder to entertain in ones own life, considering the number of variables that come into play with Death, it is not always that simple.

Lastly, I would like to talk about Irvin D Yalom, who is an existential psychiatrist and author at Stanford University. Recently, I listened to one of his audiobooks called ‘Staring at the Sun’, although once more, I skipped to those parts that interested me for the blog. Yalom states that although the self awareness that us Humans have, is a treasure, it comes with the price of mortality, and all its wounds. Our lives, individually, and our entire existence, is shadowed by the knowledge that we will inevitably die. Irvin Yalom believes that most of our anxieties are linked to the fear of death, which manifests indirectly and in many variations. He speaks of Gilgamesh, the Babylonian hero who reflected on the death of his friend: “Thou hast become dark and cannot hear me. When I die shall I not be like Enkidu? Sorrow enters my heart. I am afraid of Death”. Yalom finds that ancient wisdom, notably Greek, helps many of the individuals he encounters who are struggling with Death Anxiety. He speaks of Everyman, in the medieval morality play, who dramatises the loneliness of Deaths encounter. In Everyman’s allegorical tale, he is visited by the angel of Death, and asks it if he can bring someone along with him, to make his journey less lonely. The angel of death replies “Oh yes – if you can find someone”.

There is a slight dark humour in the next part of the tale, or at least that I think, where each and every single person who has loved him and who he has loved, seems indisposed and cannot join his journey… they are all afraid, and do not want to face it unless they are forced to (naturally, and understandably). In the story, even metaphorical figures like Beauty, Strength and Knowledge, refuse his invitation. In the end, as he accepts his final lonely journey, he finds a companion who is willing to accompany him into death: Good Deeds. The moral here, is that you can take with you from this world nothing that you have received, only what you are given. Interpretations of this drama suggests that your good deeds, your virtuous influence on others that persists beyond yourself, may soften the pain and loneliness of the journey into Death.

I think that we, as humans, are not only afraid of Death, naturally and inherently, in our lives, our losses, our anxieties, but also, in moments. I believe, that we are terrified of things ending. I have been thinking about Death and its presence in different things, not only in a person, but in the Death of a moment. We are so scared of moments ending, of things passing through us and never returning, that we avoid it as much as we possibly can. Again, if we talk about Kundera’s idea of Eternal Return, I believe that it is mastered and developed in Hope. We hope that things will continuously return, for then, moments would never slip away from us, and would always belong to us. Belonging in life is more valuable than any sort of belonging in Death, for we know not what that consists of. If moments never die, then we ourselves are not in danger of dying, because we are in fact the moments which we live. Once they are forgotten, just as those fairies, so are we.

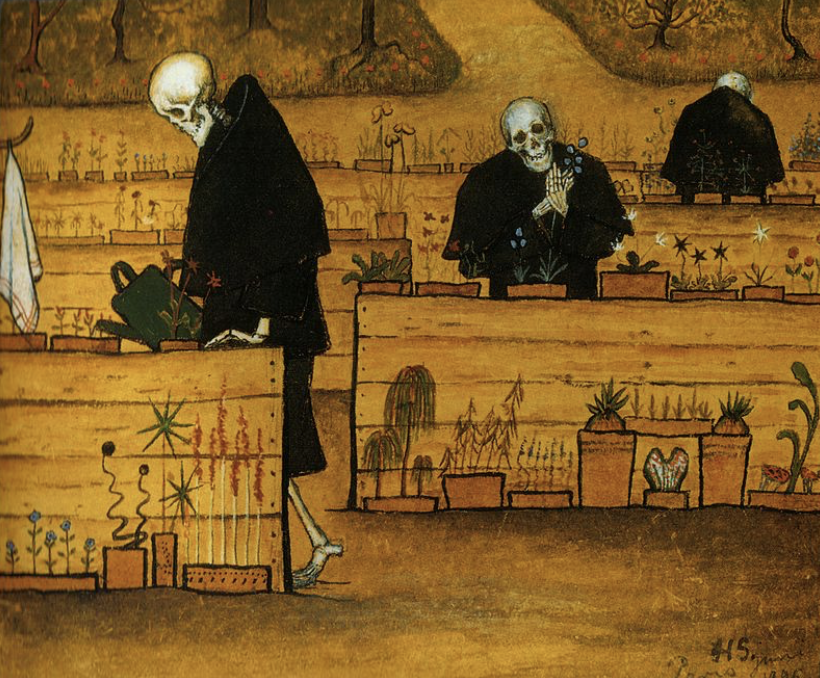

Garden of Death, Hugo Simberg

Leave a comment