Remarks by Siri Hustvedt

And notations of my own

“Without a viewer, a reader, a listener, art is dead.”

It begs the question, who do we make art for ? A lot of artists will tell you they make art, firstly, for themselves. This is especially the case in the beginning, when the audience is non existent anyway. Making artwork for yourself needs to be fulfilling enough in the initial stages, before you progress onto an audience. However, this is very similar to the falling tree theory; with no one around to hear it, does it make a sound? When there is nothing on the receiving end, then the initial ‘thing’ becomes non existent. Like a charging cable: connect the phone and it’ll charge, disconnect it, and the electrical charge has nowhere to and therefore, ceases to exist.

If art is ‘conversation’, then ‘conversing’ alone can only be eternal, with external stimuli. With an artwork, this moves through different stages as it moves amongst different audiences. If the audience remains variable, then the conversation never dies, and the artwork lives forever. Should the conversation come to a halt, so too would the artwork. The cycle is fuelled by those who receive it; those who spark questions, debates, confusions, clarities, and ultimately, inspirations. There is only so much one can produce, in a cycle that consists solely of themselves. You become a one way system, slowly emptying, without redress. So yes, eventually, with no one to receive it, art would die.

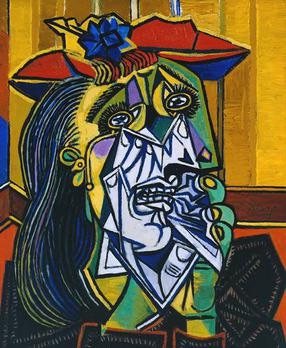

“The visible hand she holds out, with its thumbs and two fingers, has nails that resemble both knives and talons. There is a dangerous quality to this grief, as well as something faintly ridiculous. Notice: her ear is on backwards.” (Regarding Pablo Picasso’s ‘Weeping Woman’)

Is Picasso mocking her ? Making her seem overdramatic and emotional ? This seems like a typical male assumption of female grief. By putting her ear on backwards, the artist transforms her, subtly, into an unreliable narrator; rather than believing the painted, we believe the painter.

Hustvedt remarks that throughout the vast expanse of Picasso literature, the women are always referred to by their first name, including a great American writer and friend, Gertrude Stein. Intimate male friends however (famous or obscure) always merit surnames. To Picasso’s biographers, there is little doubt to his misogyny and sadism, finding fear, cruelty and ambivalence in his artworks. Angela Carter stated “Picasso liked cutting up women.”

So in fact, I remain confident about ridicule being added to a woman’s grief as a way to undermine her.

Regarding Willem DeKoonings’ ‘Women’ painted series: “But what if they had been created by a woman ? Obviously she would have had to deal with her own mother, and therefore with herself, which is a lot less funny. A woman would have to identify with the woman as her mother and as herself. Does this identification become a kind of mourning that prevents comedy ?”

Here I’d like to bring up Freud’s ‘Electra Concept’ (which is also picked up on in The Unbearable Lightness of Being) tackling the complex relationship between mother and daughter, which is repeatedly represented throughout history and the arts.

A tauntingly difficult subject to approach, considering a majority of us are too scared that we might offend people, or the world, choosing an aversion to the truth, wiggling our way around topics that make us uncomfortable or may change the course of the way things are right now. Far easier to live in a beautiful world of shallow unreality, rather than facing and discussing the things that truly matter.

Mother/Daughter relationships are deeply fixed into history, brought up precariously but majorly in the arts, that tackle it with subtlety, curiosity, and horror.

“We consume other artists, and they become part of us – flesh and bone – only to be spewed out again in our own works.”

Really, this perpetuates the idea that we never truly make anything unique, original or new. Everything is more of an accumulation, contradiction or combination or all which already exists. Ultimately, it is subconscious (although it is done consciously too) whereby our minds ingest all the things we see around us and use them in turn as varying forms of inspiration.

I’m hesitant to choose one conclusion to this argument. I think we are a reverberation of the world around us, however, this only occurs in the manner we choose. Our unique touch gives our inspirations the strength to become their own interpretations. In this way, they are unique, and really, Hustvedt isn’t stating the opposite.

They do always say, to be a great writer, one must be a great reader. The same goes for art, no matter the form.

“In 1974, Louise Bourgeois wrote “a woman has no place as an artist until she proves over and over that she won’t be eliminated.”

Is that also the case in society? A woman has to earn her place, and once she has earnt it, just must continue to demonstrate her worth, proving that she is deserving of it.

From what I have understood of the ‘Balloon Magic’ chapter from Husdvedts’ collection of essays, there is a significant unconscious bias at work when it comes to art by woman. For example, in the last 10 years, around 80% of all solo shows in New York have been by men. Also, the highest paid price for an artwork (by a post Second World War artist) was a Rothko, sold at $86.9 million, compared to the highest paid artwork by a woman, Louise Bourgeois, was sold at $10.7 million, even though, between them, it is difficult to associate either of their works as masculine or feminine. In fact, both of these artists have displayed a blend of both socio- stereotypical feminine and masculine qualities, with Bourgeois domineering over Rothko with the socially and subconsciously typically more masculine traits. Hustvedt defines these as big, hard, strong, cerebral, tough, public, and aggressive; she does of course acknowledge the many men and women for whom this is not the case.

It seems the myriad of feminine metaphorical associations affect all art rather drastically.

“The patriarchs disappoint us. They do not see us, and they do not listen. They are often blind and deaf to women, and they strut and boast and act as if we are not there. And they are not always men. They are sometimes women, too blind to themselves, hating themselves. They are all caught up in the perceptual habits of centuries, in expectations that have come to rule their minds. And these habits are worst for the young woman, who is still thought of as a desirable sexual object because the young, desirable, fertile body cannot be truly serious, cannot be the body behind great art.”

Like in politics, an emotional woman in the arts cannot be perceived as serious. Although that seems to contradict the creative process as we know it, it demonstrates just how difficult it is to eliminate sexism in spaces that seem more gender neutral. What makes it difficult, is the attribution of genius to the artwork rather than to the artist, which is especially the case in women. Unfairly, the arts might be the only space where your emotions are not held against you, meaning they are also not perceived as your strength, but rather a fleeting moment. Once more, the woman must prove herself over and over again.

Furthermore, there exists a difficult partition between statement art, and art that exists solely in and for itself. Perhaps If it were believed that most art should be ‘great’ and topical, suggesting change, blame or courage, then perhaps the artist is imagined to be big, hard, strong, cerebral, tough, public and aggressive, or simply put, ‘male’. Therefore, once more, the woman narrator loses credibility, this time, as the painter, rather than the painted.

Perhaps then, the contradictions that come with ‘art’, become even harder for artists who face the social contradictions of being a woman, and even more, a woman in the arts.

“For the women it is often better to be old. The old wrinkled face is better suited to the artist who happens to be a woman. The old face does not carry the threat of erotic desire. It is no longer cute. Alice Neel, Lee Krasner, Louise Bourgeois. Recognised old. Joan Mitchell, shot to art heaven after her death. And remember this: the great women are all cheaper than the great men. They come much cheaper.”

Once sexual desire is removed from the woman, she becomes free in the eyes of society. She is at liberty to become whatever and whomever she would like to be, now that she is no longer considered a threat, nor something to conquer. She now belongs to a different category all together.

In an attempt to weaken the young woman, man accidentally made the older woman stronger, in his disregard for her altogether. The man mistook the absence of sex for absence of power, but ultimately, and one again, he is mistaken. Without sex, man has nothing on woman.

Bourgeois speaks of herself in the third person: “They wanted nothing to so with that young woman. They were blind to her genius, a genius that was there early, in the works she was making when she was in her thirties, as good as — indeed better than — many of the period’s art heroes.”

Hustvedt says: “Even if she is successful, she is outside. It is still woman’s art.”

Leave a comment